What is educational equity? And how can schools achieve it?

Imagine if Australia’s best companies and jobs were pooled together in one part of Sydney. Then, a 1,000-metre high wall was erected around them… but only for people from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Provided they have the right skills, other people can apply for the jobs without worries. But because of educational inequity, disadvantaged people have to scale the mammoth hypothetical wall before being able to apply – just because they grew up in a remote part of the country or a low-socioeconomic suburb. Having a well-paid, successful career – and the confidence and well-being that can go along with it – is infinitely harder for them. To bring down the wall, they need the same learning opportunities as everyone else, regardless of their post code, skin colour, or the wealth of their parents.

They need educational equity.

What is educational equity?

Educational equity is giving every student the same opportunities to succeed. Take a simplified classroom of just three new primary school students:

- Sam, a girl from a wealthy family who has had lots of early childhood education.

- Zhang, a boy from a moderately-wealthy family.

- David, a boy from a poor family living in a high-crime neighbourhood.

In this scenario, there’s a good chance that Sam will have better foundational literacy and numeracy skills than the two boys, because of her family’s wealth and enthusiasm for education. Similarly, Zhang will probably have stronger skills than David. Their backgrounds and social circumstances strongly predict their abilities before they even start school.2

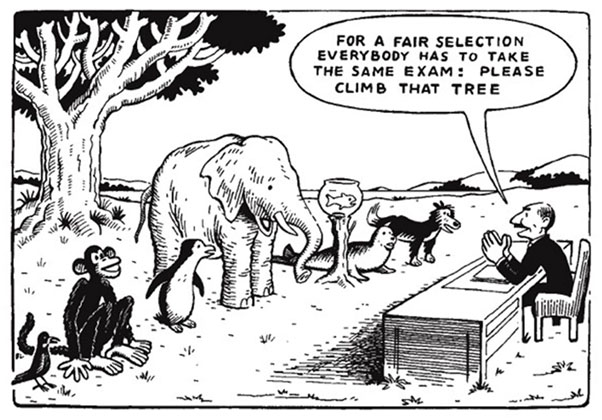

To provide these three students with equitable education, they each need different levels of support. Teachers know that education isn’t one-size-fits-all. Every student has unique needs and the only way to provide them with a fair, inclusive education is by recognising and addressing these needs. When this happens, everyone has the same opportunities to succeed, regardless of who they are or where they live.

“Every student has different needs. And to provide them with equitable education, they need different levels of support.”

There’s an important distinction to make here: trying to provide equitable opportunities is not the same as trying to provide equitable outcomes. Learning opportunities can be created by giving different students more attention, unique tasks, and tracking their performance (among other things). Learning outcomes can only be achieved by the students themselves. As unique individuals with free will, their outcomes cannot be made equitable. Instead, making opportunities more equal will naturally lead to better outcomes, achieved through their own hard work and perseverance. This helps them build a sense of autonomy and confidence and increases their chances of becoming lifelong learners who strive for excellence. By having the right opportunities and support to succeed, they can realise their full potential.

Educational inequity is present when certain groups of students don’t have access to the same educational opportunities, leading to poorer outcomes. Professor Laura Dean from Murdoch University in Perth breaks the disadvantage down further:3

- Opportunities – giving students the resources they need: skilled teachers and support, equipment, etc.

- Experiences – giving students the same opportunities for engagement, good relationships with their peers, and helping them to develop a sense of belonging at school.

- Outcomes – giving them the same learning opportunities that help them achieve closer outcomes to their more advantaged peers.

When this trifecta is achieved, education can be considered equitable. And the stakes are huge. Studies show that a person’s quality of education correlates with their quality of life. They tend to be healthier, happier, and live longer. Educational equity predicts how well they do in their careers, how financially secure they are, how healthy they are, and how much they contribute to society.1 People feel more connected and trustful of each other, and have the confidence necessary to innovate.

In essence, educational equity creates a fair, egalitarian, thriving society, where social mobility is possible because the most vulnerable children don’t have to scale immense barriers to access the same opportunities as everyone else. It smashes down the wall for everyone, where disadvantages are handled how they should be: with more care and support.

“Less-educated adults tend to face the highest unemployment and inactivity rates, as well as the lowest and most rapidly declining relative wages, on average. That, in turn, can lead to a wide range of social problems, including poverty, poor health and crime.”2

– OECD, Equity in Education

When educational equity is achieved, it’s no longer possible to predict a student’s success based on their background or where they live (known as “place poverty”). Their career prospects are not crippled by a cavernous achievement gap; their confidence and well-being not built on shaky ground. Instead, students can enter their first workplaces with confidence, equipped with the skills they need to thrive.

What is educational equity like in Australia?

Australia’s education system is far from equitable.

More than 1.5 million people in Australia are classified as deeply or very deeply disadvantaged, with one in six children living below the poverty line.4 The poor communities where they live also have poorer educational opportunities. Around 51% of disadvantaged students in Australia attend disadvantaged schools, which sets them back 86 points on their mean assessment scores – around 3 years of schooling.1 They are subject to a double disadvantage through no fault of their own.

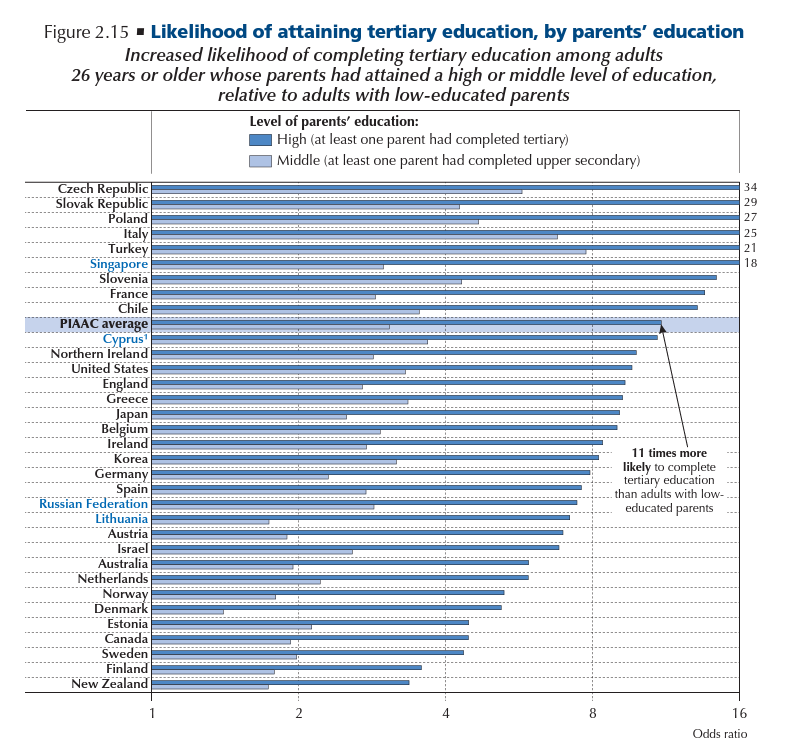

In a 2023 review of the National School Reform Agreement, the Government’s Productivity Commission found that, on average, students outside major cities are 1.75 years behind in literacy and two years behind in numeracy.7 Without these crucial foundational skills, their chances of academic success are diminished. Their parents are much less likely to be tertiary-educated, and as a result, these children are six times less likely to gain tertiary education themselves, eliminating even more career opportunities.

Image from OECD, Equity in Education report2

Image from OECD, Equity in Education report2

But there’s hope. A huge study in 2018 by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that social background doesn’t have to predict educational achievement:

“The fact that the impact of social background on educational success varies greatly across countries shows there is nothing inevitable about disadvantaged students performing worse than more advantaged students. Results from education systems as different as Estonia, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Vietnam show that the poorest students in one region might score higher than the wealthiest students in another country.”2

– OECD, Equity in Education

With the necessary Government policies and programs, as well as the right skills, knowledge and initiatives from teachers and schools, Australia can make its education system more equitable and create brighter futures for its children.

Educational equity vs equality: what’s the difference?

People often confuse educational equity with educational equality, but there is a distinct difference.

With educational equality, everyone would be treated the same regardless of their circumstances. This may sound fair, but every student has unique needs, so giving them the same support may not lead to better outcomes for them.

With educational equity, each student gets the support they need to succeed. It’s a much more inclusive approach that leads to better outcomes for all.

What can your school do to improve educational equity?

“We must abandon standardised, talent-sorting education and embrace individualised talent-developing education.”

– Dr. Lindsey F. Ott, educator5

No doubt about it – educational equity is tough for schools to achieve, especially schools without adequate funding. Providing disadvantaged students with the personalised education they need to succeed takes a lot more time, which means more teachers and support staff to handle the work. Without adequate support, many teachers start their careers excited and depart exhausted.6

However, while funding is decided by government budgets, policies and initiatives, making it extremely difficult to influence, there are other things you can do to make your school’s education a little more equitable for disadvantaged students.

1. Take a “whole school” approach

Big challenges often require big plans. To make your school’s education more equitable, it should start at the school level, with annual quality improvement plans that are broken down into manageable actions. While the teaching ultimately comes down to the teacher, without this strategy and its individual actions to guide them, creating a more equitable education can feel so overwhelming that it’s (understandably) avoided.

With this broad strategy in place and the smaller targeted improvements clearly outlined, teachers can start to implement them, monitoring their success as they go. This approach to meeting the needs of students and the wider community is far more effective and sustainable because it actually feels achievable.

2. Create a positive learning environment

As smaller, more vulnerable humans, safety is a chief concern for children. If they’re in a classroom environment that feels negative for whatever reason – a frustrated teacher, unkind classmates, too much pressure – their defenses can flare up and learning becomes difficult because they’re stressed.

Creating a positive classroom environment helps them relax and engage with their learning. They trust their classmates and teachers and build good relationships with them. They feel valued and confident enough to wholeheartedly be themselves. And most importantly – they feel safe enough to focus on the tasks at hand and do a good job of them.

Some effective ways to build a positive learning environment include:

- Building good relationships with parents and students, so you can better understand their needs and circumstances (more on this below).

- Setting clear, enforced rules for behaviours so students know where they stand.

- Positively reinforcing effort, not intelligence (growth mindset).

- Running social emotional learning activities like mindfulness, to help students better understand their inner lives.

Positivity can have a big impact on your school’s staff too. If they believe that their hard work positively affects students, the school is likely to achieve better outcomes for them. If you haven’t already heard of it, this is known as “collective teacher efficacy” and is a powerful phenomenon with studies to back it up.

3. Set ambitious goals

“Easy goals just don’t have the same driving force as challenging goals, and this is true for students across the entire spectrum – the highest and lowest achievers.”

Goals are like motivational rockets. They provide us with clear objectives that guide our actions and fill us with energy, but the amount of energy can vary depending on how ambitious they are. Easy goals just won’t have the same driving force as challenging goals, and this is true for students across the entire spectrum – the highest and lowest achievers. Be cautious of setting low expectations of your disadvantaged students, as it can become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

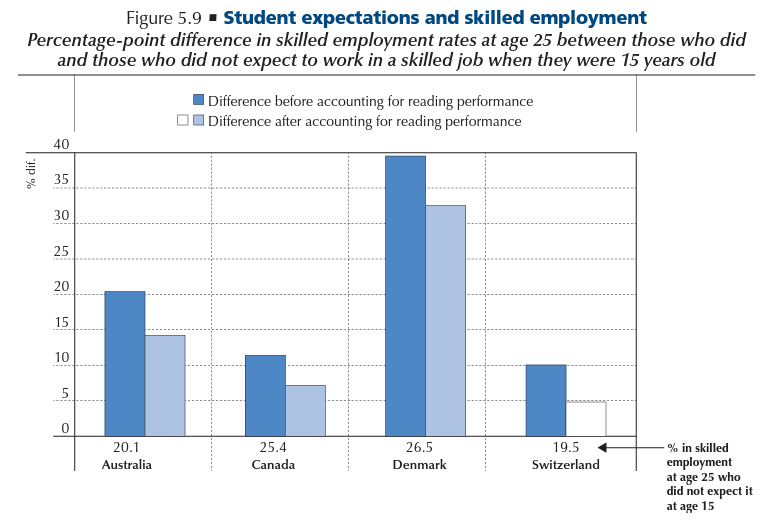

Research shows that students with clear visions or goals for their future are more likely to achieve them – around 15% more successful in Australia (see image below). Help your students set ambitious goals and visions they can strive towards, suited to their specific skill levels. It can make a noticeable difference to their success.

Image from OECD, Equity in Education report2

Image from OECD, Equity in Education report2

4. Consider annual benchmarking tests

Identifying your students’ needs through assessment is a crucial part of equitable education – without it, you simply won’t know how quickly they’re progressing. And there’s one type of test that can enrich your regular assessment schedule and help you build a more vivid picture of your students’ needs: benchmarking tests.

These annual progression monitoring tests can be norm-referenced against thousands of other students, giving you a precise benchmark of where they sit for core subjects like English, Maths and Science. You’ll get a breakdown for each individual skill level too, helping you to tailor your teaching strategies.

Reach is one example of benchmarking tests that offer this kind of in-depth performance analysis. As part of our DEEP program, supported by the University of Sydney, we’re offering a number of free tests to NSW schools in low socioeconomic, outer regional, remote, very remote and Indigenous communities, to help you close the gap and provide the best education you can for your students. Please get in touch if you’d like to apply.

5. Invest in professional development

“In more than a third of the countries that participated in PISA 2015, teachers in the most disadvantaged schools are less qualified or experienced than those in the most advantaged schools.”2

– OECD, Equity in Education

In Australia, many disadvantaged schools are located outside major cities with much smaller pools of working teachers. They simply can’t hire the same level of talent as their city counterparts, which widens the skills gap in their students even more.7 After all, the quality of your students’ education is only as good as the skill of your educators.

If this sounds familiar, a viable option is to upskill your current staff as best you can; to reduce your teachers’ own skill gaps and loosen your dependence on external talent. Be sure to organise as much professional development as you can, in both formal sessions like workshops, presentations and conferences, as well as informal sessions like peer-learning, observation and coaching. Quality professional development is especially important for new teachers, who need as much support as you can give them.

6. Build strong relationships with parents

When teachers have good, trusting relationships with their students’ parents, they can be much more influential. They can reinforce the immense significance of education for their children’s futures and encourage them to support their learning in any way they can: helping with homework, completing educational activities together, and validating and supporting them in their emotional lives.

Together, you can help their children develop positive attitudes towards learning, which can do wonders for their progress. If they are disadvantaged children at a disadvantaged school, strong relationships with parents can really help to make their children’s education more equitable.

References

- 2022, Equity and Excellence, Department of Education

- 2018, Equity in Education – Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility, OECD

- Laura Perry, 2017, Educational disadvantage is a huge problem in Australia – we can’t just carry on the same, The Conversation

- Improving Educational Equity in Australia, UNSW Sydney

- Lindsey Ott, 2018, Solving the Achievement Gap Through Equity, Not Equality, TEDx

- Pasi Sahlberg, 2022, New Education Minister Jason Clare can fix the teacher shortage crisis – but not with Labor’s election plan, The Conversation

- 2022, Review of the National School Reform Agreement, Australian Government Productivity Commission

- Peter DeWitt, 2019, How Collective Teacher Efficacy Develops, ASCD

Matt has a diverse educational background, specialising in transforming school learning cultures and enhancing educational practices. He started as a secondary school educator in South Australia, with a focus on supporting vulnerable students and promoting trauma-informed teaching practices. Matt also excelled in leadership roles, which included the role of Principal Consultant for the Department of Education. As Head of Parndana Campus in South Australia, he helped Kangaroo Island Community Education to win three consecutive titles as Australia’s Regional School of the Year (2018-2020).