Diagnostic assessments – teacher’s guide & examples

When you step into a doctor’s office with a problem, they usually diagnose it by asking questions and using tools like thermometers or stethoscopes. When students step into a teacher’s classroom, the most important “problems” the teacher must diagnose are the students’ skills and knowledge. For a particular topic or subject, they need to understand what their students know about it and what practical abilities they can demonstrate for it, so that the teacher knows what areas to cover from the curriculum.

As a teacher, diagnostic assessments are the tool you will use to get this information. In this article, I’ll explore the ins and outs of these crucial measurers of knowledge, including the various types, examples of each, and more, so you can understand their significance and how to use them effectively.

What are diagnostic assessments?

Diagnostic assessments are a type of test that diagnose students’ depth of knowledge and clarify misconceptions, so that teachers know which topics they need to teach (or re-teach) from the curriculum. They are usually set for individual classes to help with lesson planning, but for larger cohorts, they can help to create entire subject programs. They can also help you set accurate targets for students, identify which intervention strategies may be needed for lower-level students, and pinpoint any higher-level students who would benefit from delving deeper into particular topics. On the downside, diagnostic assessments can take a lot of time to run, mark and analyse.

Despite being time-consuming, diagnostic assessments are a fundamental tool for identifying your students’ learning gaps. Without them, you may find yourself teaching content that is too easy for the average knowledge of your class and be confronted with rows of bored faces, or topics that are too advanced for them where knitted brows and gloomy expressions are the order of the day. Like Goldilocks’ porridge, diagnostic assessments allow you to teach the content that is “just right” for your particular students. And when triangulated with data from other tools like benchmarking assessments, you can build a vivid picture of your students’ knowledge levels.

Diagnostic assessments can be used to test a broad scope of knowledge, including individual topics, groups of topics, or in some cases entire subjects. You may be starting a new unit on geometry and want to learn your class’s average knowledge and possible misconceptions before creating your lesson plans. Or you may be starting a new school year and want to know their average knowledge of an entire subject like maths, to decide whether you should teach the concepts and skills at their grade level or fill their knowledge gaps by covering concepts and skills from previous or foundational years. Regardless of the scope, diagnostic assessments will help you discover what your students do and don’t know, so that you can create effective lessons plans that are precisely aimed at their current level.

Because diagnostic assessments are often set before teaching starts for a topic or subject, they can be known as “pre-tests.” According to the New York Times, these types of tests have shown to prime students’ brains for the information that follows, which helps to solidify their knowledge.1 They are often combined with identical “post-tests” after the program has been taught. For students, studies show that they can increase learning and retention (known as the “testing effect”)2, and for teachers, they provide you with accurate before and after pictures of your students’ knowledge. This helps you to understand the effectiveness of your learning programs and provides you with clues for improvement. There’s also the important benefit of showing your students what happens when they work hard in class: they learn new concepts and become smarter! This can be extremely gratifying, motivating them to keep on succeeding and even helping them develop a lifelong love of learning.

10 diagnostic assessment examples and types

Diagnostic assessments are typically informal tests that are prompted by teachers (rather than being state mandated). This makes them unique to the school, where you can decide which types of assessments are suitable for your students and how often to set them.

There’s a wide variety of diagnostic assessments types to choose from, including:

1. Quizzes

These are simple multiple-choice tests that are criterion-referenced to determine the right answers (similar to many ICAS assessments). They may also be based on specific curriculum outcomes, use scaled answers such as “strongly agree” to assess knowledge, or contain “hinge” questions to identify misconceptions.

During my time as a teacher, I used to run casual quizzes where I’d put a series of quick statements on the board and ask my students whether they agreed with it using a thumbs up / thumbs down voting system (similar to anticipation guides, covered below). This kind of exercise is a much less formal diagnostic, where we can incorporate discussion and then segway nicely into the lesson.

Quizzes are quick to mark and provide direct information on your students’ understanding of specific topics.

2. Surveys

A straightforward conversation where you ask your students what they know about certain topics. As you work through each topic, the number of hands raised and the quality of answers can give you a rough indication of their general knowledge and help to guide you on which topics should be taught next.

3. Discussion boards

These are similar to surveys, but instead you ask students to come up to the board and write what they know. This can take the form of a “graffiti wall.” You can recognise possible learning gaps by what should be on the board but isn’t, as well as any misconceptions that your students may have.

4. Informal debates

As Socrates knew over 2,000 years ago, we can learn much from conversation and dialogue. Asking your students to casually debate a topic can help them to see it from various angles, with each side bringing their arguments, supportive reasoning and their passion to the conversation. More importantly, for the sake of diagnosing their knowledge, it also gives you a respectable summary of what they know about the topic being discussed.

5. Checklists or rubrics

|

1 |

2 | 3 | |

|

Volume |

Very quiet and almost impossible to hear | Quiet, but can just about hear | Ideal volume, everyone can hear clearly |

|

Fluency |

Stopping and starting every few seconds | Occasional stops and starts | Consistent, good speed with few stops and starts |

| Clarity | Lots of mumbling, difficult to understand | Most words pronounced clearly, but some mumbling here and there | Great pronunciation, very clearly understood |

Rubrics and checklists are ideal for testing skills like reading. In this example, you might ask students to verbally read a suitable text for their year level, and as they do so, you can assess their skill using reading rubrics like volume, clarity and fluency, and decide where to focus your efforts to improve their reading abilities. Or a PE-teacher may want to check what their students know about the fundamentals of a sport such as cricket, with listed items including things like “touching the wicket,” “bowling” and “catching,” which they can dedicate practice to if needed.

6. KWL charts

These are charts broken down into three columns – what I know, what I want to know and what I have learned – which are drawn on the board and filled out as part of a conversation you have with your students. It can help to activate their prior knowledge of a topic, get them curious about what is going to be taught, and when the final column is completed after the unit or lesson is over, it summarises the content and can make them feel satisfied with learning the new information.

Some teachers also like to include an additional section – how will you learn it (which makes it KWHL) – to encourage students to think about how to research and discover the information.

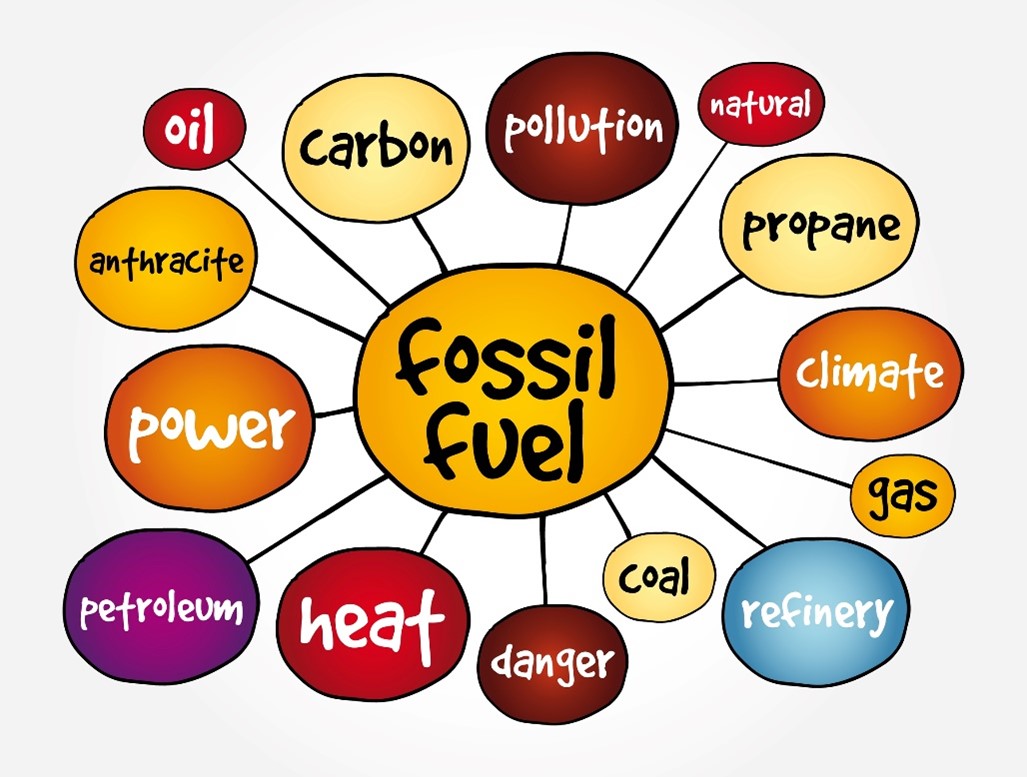

7. Mind maps

Provide students with a central topic such as “biological sciences” and ask them to surround it with what they know, with as many associative layers as they need. This can be done individually or as a group on the board.

8. Entry and exit slips/tickets

Students fill out simple entry slips with scaled questions such as “how well do you understand the material,” long-form answers about specific topics or questions that are centered around the learning intentions for the lesson, or alternative information-gathering formats to assess their knowledge. When the class is done, they fill out similar exit slips to tell you what they’ve learned. These are a simple form of pre- and post-tests.

9. Anticipation guides

|

Plants and flowers produce offspring through eggs Do you agree or disagree with the above statement? Why? |

|

| Before lesson | After lesson |

|

|

|

Anticipation guides are statements that students read – for example “plants and flowers produce offspring through eggs” – and answer with why they agree or disagree. They do this before you start your lesson, which helps to uncover misconceptions and assumptions that you can correct, and after the lesson, which can give them a sense of satisfaction at having learned the information.

10. Off level assessments

These are tests that contain topics from a different grade level. If your class (or a sub-section of your class) seems particularly advanced, and the subject’s topics carry across multiple grade levels, you may decide to test them on some of the following grade’s topics to determine just how advanced they are. If the assessment shows that they have a good depth of knowledge for the topics, you can consider teaching them laterally to solidify their knowledge further, testing more sophisticated skills like higher-order thinking and problem-solving. By contrast, you may feel the need to test some students on topics from the grade below to see where they sit and identify whether anything needs to be re-taught.

Any of these diagnostic assessment types can be created from scratch by yourself, lifted from subject textbooks, or downloaded from credible websites. The important thing is that they deal with the curriculum topics that your students need to learn, and that they diagnose all skill levels – easy, average and hard – to ensure they cover the often-broad knowledge range. Marking these types of assessment also requires vigilance and professional judgement as to why a student may have answered in a particular way – do they have misconceptions / intuitive theories that fly in the face of the curriculum? Are they demonstrating distinct knowledge gaps that need to be filled? These things can require a keen eye to spot.

Diagnostic assessments are a type of low-stakes assessment, which means they don’t usually contribute towards grades. For the types that feel more intimidating, such as traditional sit-down assessments, you’ll want to do everything you can to lower your students’ stress levels so they can think clearly and provide you with more accurate results. However, the purpose of the assessment is to help you discover what they need to learn. So there’s no right or wrong answers. And more importantly – learning should be fun! Many types of diagnostic assessment don’t have to feel like tests, and in fact, the more creative and fun you can make them, the more engagement you’ll get from your students, and the more excited and confident they’ll feel. I once completed an assessment on atoms and molecules where I asked students to give me examples of items that are in their solid, liquid and gas states, and was able to determine their understanding by their answers. For another assessment, I’d create two lines on the floor using metre rulers – one for true, and one for false – and after being asked a question, students would decide which line to walk to while justifying their choice. We’d also play Bingo where students would have various cards with answers, and they’d have to find the correct answer to the question being asked (e.g. they’ll circle their card that has 4 on it after being asked, “What is the square root of 16?”). These kinds of activities can really appeal to the various types of learners too, whether kinaesthetic, visual or auditory, and reinforce the idea that learning is fun.

Diagnostic, formative and summative assessments – what are the differences?

From these assessment types, the two broad groups are formative and summative assessments. Certain words in their names can help you to remember what they are used for:

- Formative assessments are primarily used to identify learning gaps. They help you to form your teaching plans based on what your students know. They are also for learning rather than grading.

- Summative assessments provide a summary of a student’s knowledge for the topic or subject, given for grading purposes. They show you how much they have learned.

Formative assessments take place during learning to help you teach the right topics, and summative assessments show you how successful their learning has been. As you might have guessed, diagnostic assessments are a type of formative assessment. The key difference is that diagnostic assessments are usually completed before learning takes place to diagnose students’ knowledge, and formative assessments are used throughout the learning cycle to give you regular feedback on their knowledge and allow you to change your teaching strategies to suit their needs.

Diagnostic assessments – summary

Diagnostic assessments help illuminate the depth of your students’ knowledge on a topic so that you can decide what to focus on in class. They are a crucial tool for teachers, and encourage a “time-free” curriculum where your students’ progression through their learning journey becomes more important than where they “should” be at a certain age; where you dismiss expectations by regularly analysing the learning needs of your particular students so that you can pinpoint not only what to teach them, but when to teach it to them. This helps to open doors of opportunity for your students and really makes a difference.

I hope this article has helped you to better understand the importance of diagnostic assessments. Good luck!

Nardin is a former primary school teacher of 10 years. During her time as a teacher, she served as Head of Years for K-2, was a trained NAPLAN marker, and was part of the team that wrote the 2021 NSW English Syllabus 3-6. She is currently an assessment consultant for ICAS and Reach.

References

- Benedict Carey, 2014, Why Flunking Exams Is Actually A Good Thing, The New York Times

- Mark A. McDaniel, Janis L. Anderson, Mary H. Derbish, Nova Morrisette, 2007, Testing the testing effect in the classroom, European Journal of Cognitive Psychology (Volume 19)

Tag:assessments

Written by Nardin Hanna

Written by Nardin Hanna