Formative assessments: the ultimate guide for teachers

K-12 education is a construction process where students’ skills and knowledge are gradually built up, with every preceding “block” essential to keep on building.

As a teacher, it’s your job to ensure that your students have the core knowledge they need to keep advancing through their education. You need a daily understanding of their current skills and knowledge so that you can accurately gauge their progression, and decide what to teach them next.

One of the most effective, proven ways to do this is with formative assessments (OECD, 2008).1 They’re a crucial tool in your teaching kit, helping you to provide quality education to students.

Table of contents

- What are formative assessments?

- Evidence that formative assessment works

- Formative assessment examples / types

- Formative assessment strategies for your school and classroom

1. What are formative assessments?

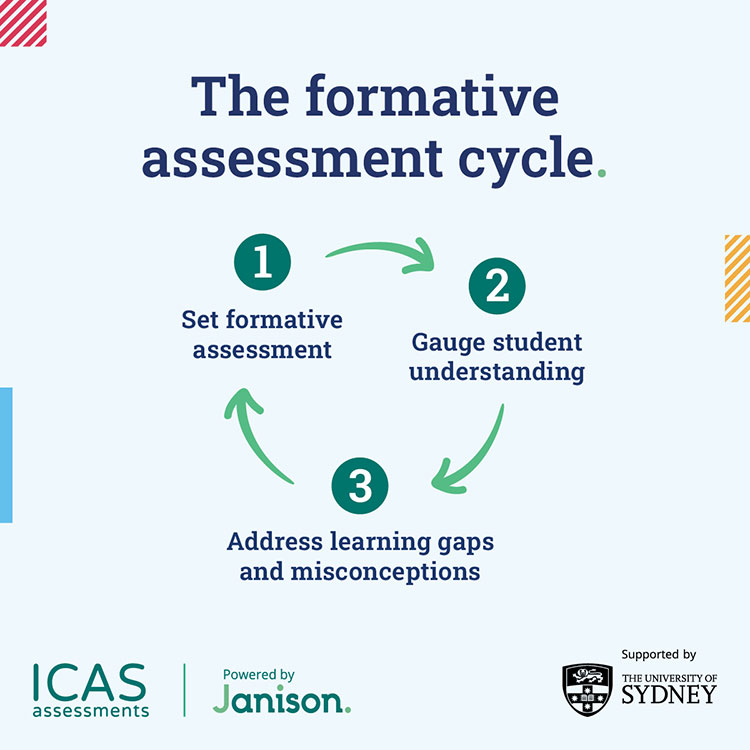

Formative assessments are regular low-stakes tests that help you gauge students’ understanding. They are “dipsticks” where you can quickly check learning as you might quickly check the oil in your car, allowing you to adapt your teaching and fill knowledge gaps while learning is still taking place.

Quizzes are a common example of formative assessments. They’re quick to create, complete, and mark, and give you a good impression of students’ understanding of the content and their progress for the unit. You can see which questions and topics they are struggling with, re-teach them, and then re-test – a rapid feedback and improvement cycle that boosts student outcomes and moves them along their learning journeys.

You can see how this differs from summative assessments like end-of-year exams. These are one-off tests used to evaluate student understanding after learning has finished, with no opportunity to improve. Their purpose is to grade. But with formative assessments, getting the right answers isn’t important because that isn’t the objective. Instead, the purpose is to provide you with continuous, fast “readings” of student progress which you use to adapt your teaching and advance their learning. Summative assessments are to grade, and formative assessments are to direct.

As you can imagine, this sets entirely different tones for the two types of assessment. Summative tests can be high-stakes with real consequences that shape students’ future opportunities. This makes them understandably anxious, which can significantly affect their performance (Embse et al., 2018).2 Formative assessments, on the other hand, are low-stakes, light-touch tests that are (ideally) designed to be fun and engaging, and to boost learning outcomes (OECD, 2008).5 Formative assessments help to improve summative assessment scores/grades (and more importantly, their education), but this doesn’t work the other way around.

To make our position clear: both types of assessment have an important place in education. They just have different purposes and effects on students. If you’d like a more detailed comparison of these two types of assessment, please check out our article here.

How formative assessments help your teaching

“Formative assessment – while not a “silver bullet” that can solve all educational challenges – offers a powerful means for meeting goals for high-performance, high-equity of student outcomes, and for providing students with knowledge and skills for lifelong learning.”1

– OECD

In essence, formative assessments help you answer three key questions:

- Are students learning what they need to learn?

- Are students learning at a steady pace?

- What should be taught next?

The answers to these questions form an objective appraisal of your current teaching strategies and lesson plans, providing clues on what needs to change. This may include the following and more:

- Change of content – formative assessments reveal student understanding, which includes any learning gaps or misconceptions they may have. With this information, you can adjust the content being taught to ensure they are learning what they need.

- Refine learning intentions – when you have a strong understanding of your students’ knowledge and skills, you’re able to write more precise learning intentions in your lesson plans, and by extension, better plans overall that accurately address students’ needs.

- Group students based on ability – formative assessments are usually given to entire classes, which reveals students’ both individually, and as a whole. If assessment results reveal distinct groupings of students based on their knowledge and skill, and you have the capacity to group them in your class and set unique work, that’s a much more inclusive way to teach and likely to result in better learning outcomes. More broadly, this information also helps you form separate support classes or Gifted and Talented classes.

- Change frequency of assessment – if you’ve previously identified knowledge gaps, you’ll want to re-assess after learning to ensure they’re filled. While formative assessment should be a regular occurrence in your class, the frequency should change depending on the results and other feedback you get from students.

Formative assessments in action – a quick example

“Assessment is the bridge between teaching and learning. It’s only by assessment that you know what has been taught, has been learned.”3

– Dylan Wiliam, formative assessment expert

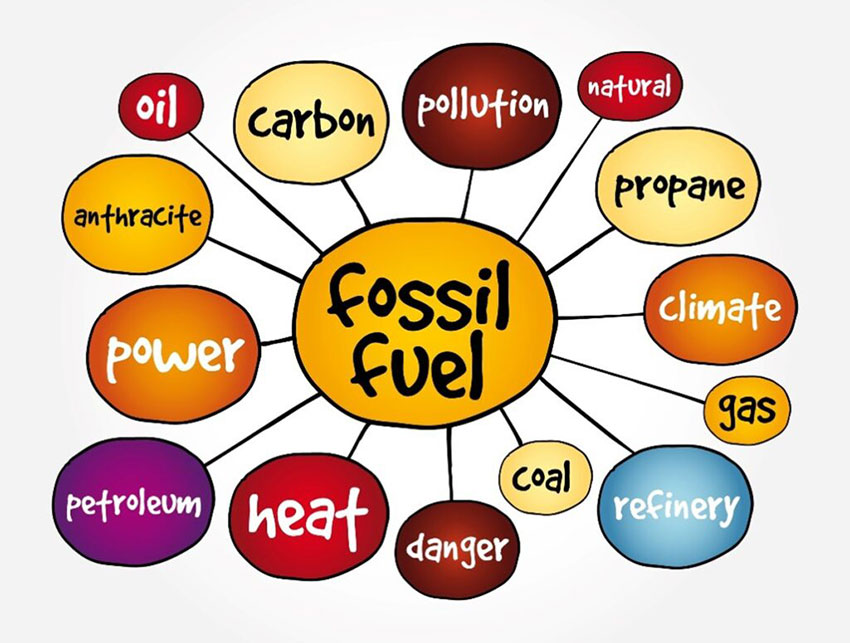

To give you an example of formative assessments in action, let’s say you’re a Year 8 Science teacher starting a new term with students, and before proceeding with the content assigned to this term, you want to check their understanding to ensure they’ve mastered the prerequisite content, allowing you to correctly build on their knowledge.

As part of this term, students are extending their knowledge of biological sciences. So you ask them to take five minutes to create individual mind maps of everything they remember about cells – a brain dump of the content they have already been taught last term. Walking around the class, you can see maps that contain organelles, membranes, nuclei, and even little drawings of cell structures. Some students have filled their A4 sheet and others have barely touched it (mental note added). But overall, your students have covered the core concepts they learned last year.

To validate this information, you’d like them to elaborate on their mind maps to ensure they actually understand (rather than just remember) the concepts, so you write a few of the key ideas on the board and ask who would like to explain it. They seem to have a good grasp of membranes and nuclei, but even with plenty of hints, nobody can accurately describe what organelles do, or how the cells of plants and animals differ. You’ve identified two clear topics that need some refreshing, which you can either teach immediately or add to your next lesson plan.

These formative assessments may have taken no longer than 10 minutes. Of course, there needs to be a good balance between assessment and instruction, but that’s the beauty of formative assessments: they are quick and sharp and provide you with objective, real-world data that effectively directs your teaching. By incorporating formative assessments into your day-to-day teaching, you have vital feedback on student learning which you can use to identify and fill their knowledge gaps, build on their knowledge, and set them up for success.

Formative assessments help students become self-learners

Formative assessments have another effect on students that can improve their education and lives immeasurably: they help them become empowered self-learners (Clark, 2012).3

This happens for two reasons:

They learn self-evaluation techniques

Many formative assessments have processes in which students assess their own work or the work of their peers. Rubrics are a good example. You can give students a marking rubric that allows them to assess their classmates’ abilities at reading aloud, as per below:

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Volume |

Very quiet and almost impossible to hear |

Quiet, but can just about hear |

Ideal volume, everyone can hear clearly |

|

Fluency |

Stopping and starting every few seconds |

Occasional stops and starts |

Consistent, good speed with few stops and starts |

|

Clarity |

Lots of mumbling, difficult to understand |

Most words pronounced clearly, but some mumbling here and there |

Great pronunciation, very clearly understood |

“By learning how to evaluate their own work, students develop the crucial meta-cognitive skills they need to progress by themselves.”

By using this rubric as a guide, they can score their classmates on volume, fluency, and clarity, and in the process, they also learn how to assess their own skills and pinpoint areas of weakness.

Informal debates are another example. You can create small groups of students and ask them to debate an issue in which they express their opinions, back them up with evidence, and listen to why their classmates agree or disagree. The conversations help them discover potential misconceptions or logical flaws, again teaching them (through modelling) how to evaluate such things by themselves.

By learning how to evaluate their own work, students develop the crucial meta-cognitive skills they need to progress by themselves. It’s giving them the proverbial fishing rod instead of a fish. They learn how to reflect, critique, review, and mark their own work, giving them a firm grip on their own learning and accelerating them to speeds far beyond what teachers can achieve by themselves. This leads to greater self-efficacy (Panadero et all., 2017)4 and success.

They’re interactive and social

Formative assessments are highly varied, interactive tasks that students engage with during class. For most students, because the assessments are hands-on activities that require their attention, this makes them more interesting than standard instruction from the teacher. Students often become enthusiastically engaged in their learning, which creates a sense of agency and responsibility for their education. When combined with learning goals, this can be a powerful tool for improving outcomes.

Similarly, formative assessments can be co-operative social activities where students are encouraged to interact with their classmates and teachers. They might be having conversations with each other, validating their knowledge before and after learning, self-assessing using proven techniques, and many other activities (see our full list of assessment examples below) in which they are active and involved. As socially-driven creatures, this can turn your students’ learning from dull chores into genuinely fun experiences where they build friendships along the way.

2. Evidence that formative assessment works

“Teaching which incorporates formative assessment has helped to raise levels of student achievement, and has better enabled teachers to meet the needs of increasingly diverse student populations, helping to close gaps in equity of student outcomes.”1

– OECD

Formative assessments have been studied extensively, and show sweeping improvements for learning outcomes (OECD, 2008).1

A comprehensive report on formative assessment by the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), backed up by numerous studies, found the practice to be one of the most important interventions for promoting high [student] performance ever studied (OECD, 2008).1 It’s the equivalent of taking students’ scores in an average performing country and lifting them into the top five best performing countries (Beaton et al., 1996, Black and Wiliam, 1998)5,6.

The OECD report shows that formative assessments:

- Make education more equitable. They lift the performance of every single student, including those who are underachieving.

- Improve school attendance. Formative assessments tend to be fun and engaging for students, which makes school much more enjoyable and reduces absence rates.

- Help students retain what they’ve learned. Assessments tap into the “testing effect” – a phenomenon in which the act of testing also boosts learning. Trying to recall information from memory is a highly effective way to learn (Brown et al., 2014).9

- Help students become self-learners. They are more involved and engaged in the learning process itself, discovering the mechanics behind learning and self-evaluation and how they can do it themselves.

- Help to clarify misconceptions. These can be immediately corrected during learning, before they are consolidated into long-term memories during sleep (Klinzing, Niethard and Born, 2019).11

Aside from the OECD report, there are numerous studies where formative assessment has proven its worth. A 2021 meta-analysis of 32 studies found that formative assessments boosted learning outcomes considerably (Karaman, 2021).11 For the core foundational skill of Writing, another meta-analysis of formative assessment experiments found feedback to be a crucial part of the process. When teachers and peers gave feedback, and students self-evaluated their own work, writing quality was enhanced (Graham et al., 2015).7

Another study found formative assessment to have a positive influence on literacy as well as maths and the arts. Helping students to self-assess provided one of the biggest benefits, as did providing written feedback on quizzes (Lee et al., 2020).8 Feedback has proven to be a crucial part of effective formative assessment, and we cover this in more detail below. For Science, high school biology teachers who completed a professional development program on formative assessment saw their abilities increase for key areas such as interpreting student ideas, eliciting questions and providing feedback (Furtak, et all., 2016).7

Finally, in a random sample of 22 Swedish Year 4 Mathematics teachers, researchers asked them to participate in a professional development program on formative assessment. After implementing their knowledge in their respective classes, their students significantly outperformed others (Andersson, Palm, 2016).10

We could go on. There’s so much evidence of the efficacy of formative assessment. It’s amazing to think that such drastic improvements can be made by introducing effective formative assessments into your classrooms (we talk more about effective strategies below).

3. Formative assessment examples / types and how they work

Formative assessments are extremely diverse. They range from generic to subject/content-specific, allowing you to assess knowledge and skills in a variety of ways, and cover the full breadth of K-12. You can pick and choose which formative assessments suit your students based on their age and the covered content.

Their variety and spontaneity can make learning much more fun for students of all ages. These are some of the more common formative assessment examples you’ll find in schools across the world.

Quizzes

Age group: all

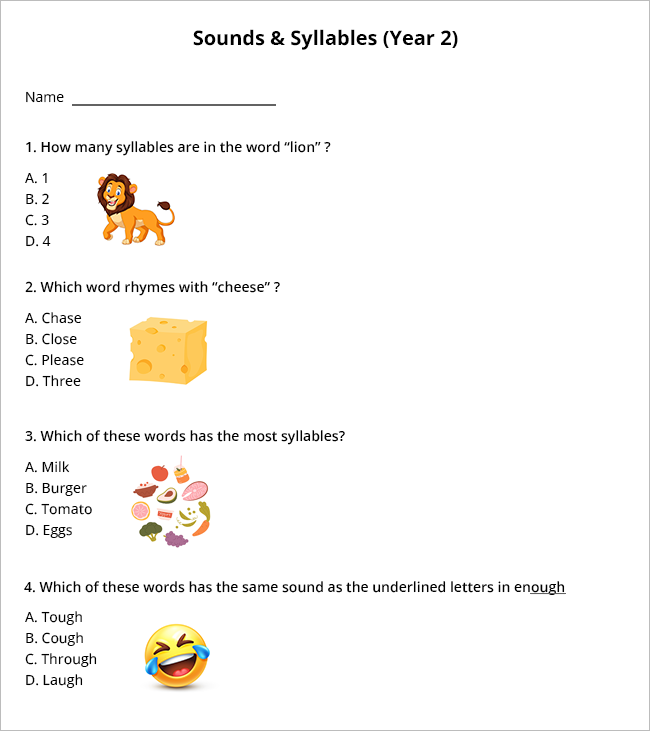

Quizzes are one of the most popular types of formative assessment, and for good reason: they’re fun, quick to create and mark, and give you a great indication of students’ general knowledge, learning gaps and possible misconceptions for a topic. They can be given as:

- Diagnostic pre-tests before starting a new unit

- Mid-unit checkups to determine whether learning is going according to plan

- Evaluative tests that check learning before the next unit starts

- Start or end of lesson check-ups to quickly assess learning

Quizzes typically contain multiple-choice questions, which make them nice and quick to mark. But they can take other forms if needed. You can also incorporate directive feedback into each quiz’s results to show students what they might do to improve.

Discussion boards

Age group: all

With discussion boards, students write what they know about a topic on the whiteboard. This could be as a mind map, graffiti wall, or another format, with students writing short words or phrases, full sentences, or even drawing pictures. It’s a brain-dump of sorts that helps you understand students’ depth of knowledge for a topic, and any potential learning gaps or misconceptions you need to address.

Brain dump

Age group: all

Brain dumps are the same as discussion boards but are completed on paper or screens, either individually or in small groups. Students write everything they know about a topic in the format they prefer, which gives you an idea of their knowledge for the topic.

Traffic light system

Age group: all

With the traffic light system, each student is given three coloured cards – one red, one orange and one green – which they need to hold up in response to a statement. Red is disagree, orange is unsure, and green is agree. You might ask them whether 10 times 10 is 200, whether day and night is created by the moon, or whether the word “running” is a verb.

When students hold their cards up, you get a visual gauge of how many students answered correctly. It’s another super-quick, fun formative assessment for younger students.

Questions / surveys

Age group: all

These are the simplest formative test of all: you ask questions to the class and assess their answers on the spot. They’re a staple of teaching around the world because they give you an ultra-fast idea of what your students know about the content already taught, so that you can refresh their memories if needed. You’ll be able to gauge their knowledge from the numbers of hands raised and the quality of answers (keeping in mind the general shyness of that particular class).

Rubrics / self-evaluation

Age group: Years 3 to 10

When students learn how to assess their own work, they’re on the road to becoming self-learners who can develop a fully-fledged love of learning. Rubrics are a formative assessment that helps them on this path. They’re a simple marking criteria that students can apply to their own (or their classmates’) work to judge their performance, and what improvements they might need to make.

As already touched on previously, an example is the reading rubric shown below. Students can listen to their classmates read aloud, give them a score for each skill, and then discuss why they gave them afterwards. The rubric is one of many tools that students can use to self-evaluate and become enthusiastic independent learners.

|

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

|

Volume |

Very quiet and almost impossible to hear |

Quiet, but can just about hear |

Ideal volume, everyone can hear clearly |

|

Fluency |

Stopping and starting every few seconds |

Occasional stops and starts |

Consistent, good speed with few stops and starts |

|

Clarity |

Lots of mumbling, difficult to understand |

Most words pronounced clearly, but some mumbling here and there |

Great pronunciation, very clearly understood |

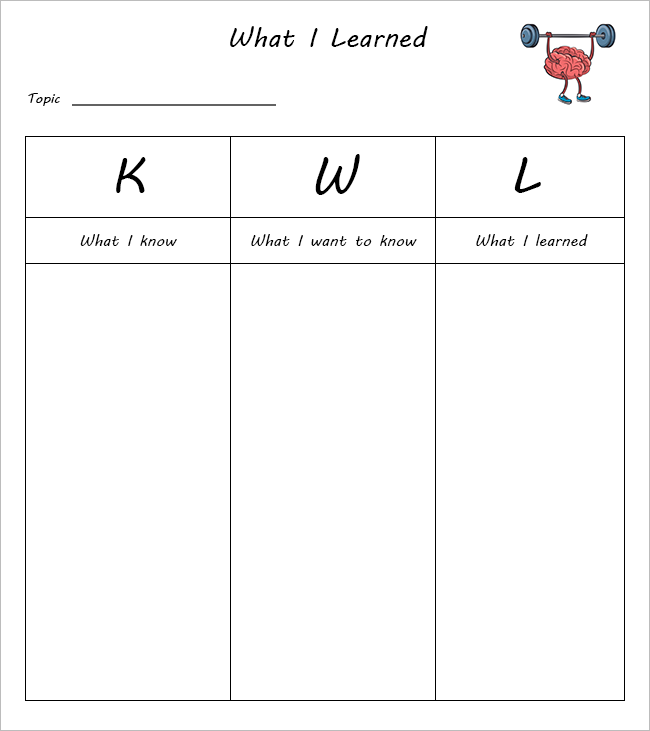

KWL charts

Age group: Years 3 to 10

KWL charts are a formative assessment that prepare your students for what they’re going to learn, get them invested in their own learning, and help them evaluate whether learning was successful.

Three columns are drawn on the board in class, from left to right:

- What I know

- What I want to know

- What I learned

For the content being taught in today’s class, students are invited to write about what they know about it, and what they want to know about it. They complete the “what I learned” third column at the end of class, showing them whether they achieved their desires/objectives. This is another simple, effective way for students to assess their own learning.

You can include an additional section if you wish – how will you learn it (which makes it KWHL). This encourages students to think about how to research and discover the information.

Think-Pair-Share

Age group: Years 1 to 9

With Think-Pair-Share, students write down their responses to a question and then discuss their answers with a partner. You walk around the room and listen to their discussions, to gauge their level of understanding of the topic. Finally, they share their answers with the class, which encourages them to reflect on the accuracy and logic of their own.

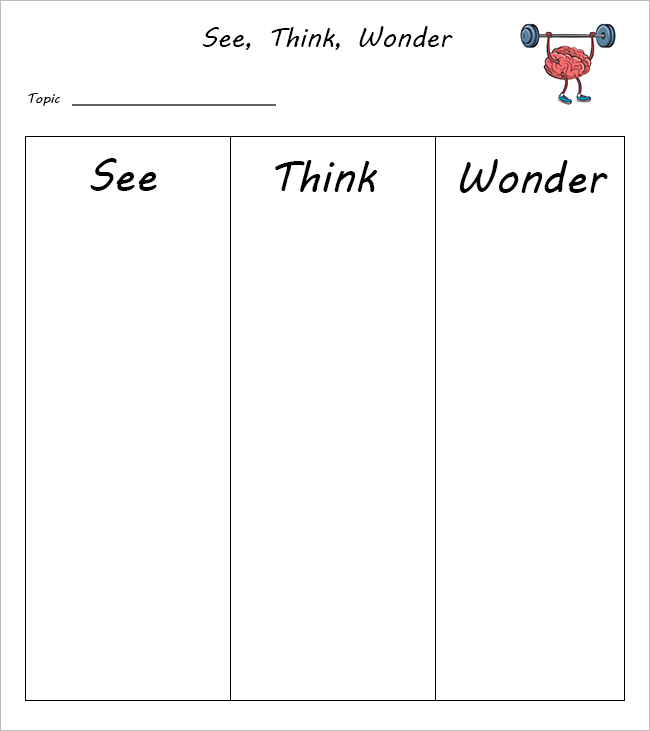

See, Think, Wonder

Age group: Years 1 to 5

See, Think, Wonder is a formative assessment that stimulates students’ curiosities and really gets them thinking about an image. They are given a photograph or picture and sheets with three columns that must be filled out:

- See – they describe what they see using descriptive language

- Think – they describe what they think is going on with the image

- Wonder – they write anything they’re wondering about the image

The task shows you the quality of their writing, their interpretation skills, their creativity, the accuracy of their observations, and more. Once done they can discuss their answers with students at their table, which encourages teamwork, or read them to the entire class.

Thumbs up or down

Age group: all

This is another quick and easy assessment that reveals general misconceptions. You offer a statement and ask them to give a thumbs up if they agree, and a thumbs down if they disagree. By judging the accuracy of their answers, you’ll know whether common misconceptions are present and resolve them if so.

For the statements, it can be a good idea to use any that your prior students have struggled with in the past.

Hot seat questioning

Age group: all

Hot seat questioning is an assessment that makes questions a little more fun. Anonymous questions are placed on a selection of seats, typically in front of class, and students are invited to select a seat, read the question aloud, and then try to answer. The rest of the class are encouraged to discuss the students’ answer and provide their own if appropriate.

The questions can vary in difficulty depending on the subject and year level. It can be an engaging, fun way to assess student learning and stimulate discussion.

Entry & exit slips

Age group: Years 1 to 6

Entry and exit slips are a simple form of pre- and post-tests, helping you understand whether content was successfully learned. Students fill out an entry slip with a question like “How does heat transfer?” and then an exit slip with the same question. This helps them to compare their knowledge before and after the lesson, which can be extremely satisfying and motivating. You can also check their answers for accuracy once the lesson is over and discover learning gaps or misconceptions that need to be addressed.

One-minute papers

Age group: all

At the end of the lesson, students are given a minute to answer a question that summarises what has been learned. For example: how does hardware and software allow people to interact with computers?

After quickly reviewing their papers, you’ll have a sense of how well they’ve remembered and understood the content, and whether you need to go over it again in the next lesson.

The limited time given to complete this task can make it stressful for some students, which impairs its accuracy. You can relax every student by telling them they have a minute, but that they can also take some extra time if they need.

Muddiest point

Age group: all

With the muddiest point assessment, students are asked to write down what they were most confused about after a lecture or other activity. You can select random students to discuss their answers with the class, have them talk about their answers between themselves, or review their answers once the class is over. If you notice common confusions/misunderstandings, you’ll want to address them in a future lesson.

Informal debates

Age group: Years 5 to 12

Informal debates between groups of two or more students can be a great way to gauge their understanding of a topic. You can assign each group member a position in the debate, ask them to present evidence of their viewpoints to each other, and have them respond in turn. It works best for more “subjective” subjects that can lack concrete explanations or viewpoints, like literature, the arts, or social sciences.

This assessment tool really taps into students higher-order thinking skills, with each side bringing their arguments, supportive reasoning and passion to the conversation.

Anticipation guides

|

Plants and flowers produce offspring through eggs

Do you agree or disagree with the above statement? Why? |

|

|

Before lesson |

After lesson |

|

|

|

Age group: Years 3 to 9

Anticipation guides are a tool that help you discover misconceptions for students. You present them with a statement like “Products have minimal impact on the earth’s environment,” and ask them write down whether they agree with the statement before the lesson begins. Once the lesson is over, you ask them to respond to the same question.

Their answers will tell you whether they have absorbed your instruction, and can also vividly demonstrate the value of teaching to them – “in the past hour I’ve learned something new and important!”

Drama

Age group: Years 1 to 6

Kids love moving their bodies, and you can use this to your advantage by asking them to “act out” certain processes in class. For example, if you want to know whether they’ve understood how gas, liquids, and solids behave differently, you can clear a space and ask them to (safely) demonstrate how they might move if they were transformed into one of these states. Or you can ask them to form expressions for how a character might feel in a story.

This exercise is not only great fun (especially for younger children), it also communicates their understanding to you.

4. Formative assessment strategies for your school and classroom

Now that we’ve covered the what and why of formative assessment, it’s time to talk about some actual strategies that you can use to implement them at your school and execute them to a high standard.

Set up a formative assessment framework

“A framework will make your formative assessments structured, purposeful, frequent, and at less risk of being dropped in favour of ‘teaching to the tests’.”

Some teachers are pressured to achieve good grades on high-visibility summative assessments, and this can come at the cost of fewer formative assessments that actually improve student outcomes (OECD, 2008).1

So it’s crucial to create a formative assessment framework that prioritises the tests, especially if they are regularly dropped in favour of summative testing. A framework will make your formative assessments structured, purposeful, frequent, and at less risk of being dropped in favour of “teaching to the tests,” especially if they are endorsed by the school leaders.

Thankfully, the OECD has completed extensive research on formative assessments, with real case studies on teachers who have successfully made them a part of their teaching and achieved strong learning outcomes for their students. These are some of their suggestions that can form the basis of your framework, adapted and summarised:

Establish a classroom culture that encourages interaction through formative assessments

Interaction is a big part of formative assessment. Students may find themselves thrusting their thumbs in the air, holding up coloured paper, drawing mind maps, having debates and more. These hands-on, collaborative types of assessment are not only more engaging for students, but it’s showing them that learning can (and should) be fun – even for the teenagers!

Make formative assessments an integral part of your classroom culture. Factor them into your lesson plans and get every student involved. Demonstrate that the tasks themselves are important because they teach them to become more self-aware, more empathetic and cooperative with their classmates, more able to make decisions, and better equipped to assess their own work. Show them, over and over, that formative assessments are not necessarily about getting a top score or beating their classmates. They’re about carving out a path for your teaching while giving them the tools they need to become fully-fledged, self-learners. Get parents involved too and try to convince them of the value of formative assessment – it should be an easy sale!

There is no such thing as “failure” with formative assessments, and with every new one completed, students will start to realise this and become more confident and happier to take risks.

Create challenging learning goals for students and track their progress, together

Goal-setting is a long proven technique for achieving better outcomes, both inside and outside the classroom. Setting challenging goals has shown to improve task performance, boost work output, and regulate choices in favour of completing the goal (Locke et al., 1968).12

In the context of formative assessments, goals should relate to mastery, not marks. Your students may create learning goals to improve their reading comprehension, to master their multiplication tables, or to run simple science experiments with clear predictions, conclusions and evaluations. With clear goals that have explicit, easy-to-understand success criteria, lessons can become more meaningful and students may find themselves more engaged in their learning – there’s a purpose and objective to what they’re doing. Rather than achieving an A+, it’s about becoming a more capable person. This can lead to greater intrinsic motivation, improved self-esteem, and a number of other benefits (OECD, 2008).1

Work with your students to set learning goals that are personally meaningful to them. Have them print them off and stick them to their workbooks. For related lessons where learning goals are shared among students, ask them to quickly read their goals at the start of the lesson, and then when the lesson is over, get them to spend 30 seconds reflecting on their progress. Did they move a little closer? What might they do better next time? This is self-learning in action, and gives them the confidence and autonomy to become lifelong learners.

Use varied formative assessment methods to meet diverse student needs

Your students are all fantastically unique. Some thrive when asked to complete quizzes. Others enjoy reflecting on what they’ve learned. Some love going up to the board and writing or drawing what they know about something.

To cater to the various needs and preferences of your students, it pays to incorporate a variety of formative assessment methods into your day-to-day teaching. This not only makes things more fun for your students, it provides you with a broader, more accurate assessment of their skills and knowledge.

Involve students in the learning process

As previously discussed, one of the most incredible things about formative assessments is that they encourage students to become actively involved in their own education, teaching them self-learning strategies they can use to grow all by themselves. These “metacognitive” strategies are a fundamental soft skill that can make a big difference to their success at school and beyond.

Try to incorporate a good portion of formative assessments that teach students the value of learning and show them how to assess their own work. These include rubrics, KWL charts, entry/exit tickets and more.

Give feedback rather than marks

Marks are important to summative tests like exams, but when it comes to formative assessments, feedback is the name of the game. It’s essential for helping students self-learn. A mark is a solitary number that tells them almost nothing; high-quality feedback is rich, specific information that tells them where to go next. It can help students to feel more motivated, better equipped, and more confident, which can almost double their growth over the course of a year (Hattie and Temperley, 2007)13.

When offering feedback for formative assessments, try to ensure that it is:

- Timely – imagine if a driving instructor only provided suggestions after you’d got out of the car? They’d be nowhere near as effective. Our short-term memories are exactly that – short – and we are much more capable of actioning feedback if it’s delivered immediately when the tasks are still fresh in our minds. Work with your students’ short-term memories, not against them.

- Specific and constructive – what specifically did the student fail at, and how can they remedy the problem themselves? That’s what your feedback should focus on. Students need to know what they did wrong and what actionable steps they can take to fix it: key ingredients for self-learning. It may be that they can’t do this by themselves because they don’t know the content well enough, in which case it needs to be re-taught.

- Motivational – starting feedback by acknowledging students’ correct answers can make them more receptive to fixing their mistakes / filling their learning gaps. By telling them they’ve done well for certain questions, it can motivate them to do well for every A pat on the back can do wonders! You can also highlight what they’ve improved on since their last assessment, helping them to see that they’re progressing towards their learning goals.

- Related to learning goals (if relevant) – what do students need to do to move closer to achieving their learning goals? What specific content should they focus on? The feedback should answer one or more of these questions for students:13

- Where am I going?

- How am I going?

- Where to next?

When providing formative assessment feedback to students, it can be based on four different things:

- The activity – how well the task was understood or performed.

- The learning process – what the student needs to do to complete the task.

- Managing their learning – how the student might need to plan or self-monitor.

- Qualities – personal qualities that the student shows, like an aptitude for arithmetic.

And finally, if providing praise as part of your feedback, it goes without saying that you should never focus on their intelligence or natural abilities. It creates a fixed mindset that can really hinder their learning.14 Instead, try to praise their effort.

Teach students how to assess their own work

Self-assessment is a key part of self-learning – a process that can work like high-powered fertiliser for students’ growth. When students are taught how to self-assess, they better understand how their answers are related to their learning goals, they’re invited to reflect on their efforts, and most importantly, they can identify what they need to do to produce better quality work.

As their teacher, you use pre-defined success criteria to assess the accuracy of their work, and they can use the very same criteria to assess themselves and their peers. As you complete the different types of formative assessment, demonstrate how you use the templates, checklists, or rubrics to mark their work, and how it shapes the judgment of what is considered high-quality. Give them samples of exemplary work and explain why it’s so good. Show them, again and again, how you use the criteria to discover potential gaps in their learning and the actions that might be taken to fill them. By modelling your own assessment and feedback processes, you help them become their own teachers.

When they get better at this important skill, students can spend time marking, discussing, critiquing and demystifying their assessment results, blossoming into self-directed learners who can take ownership of their education. You’re showing them that self-assessment is a vital part of the learning process and providing them with the tools they need to achieve great things.

The NSW Government provide some more extensive examples of how to teach students self-assessment techniques, which we highly recommend reading.

Vary formative assessments to meet students’ diverse needs

Student diversity is one of the biggest challenges to providing great education, and this extends to formative assessment. With so many different learning styles, preferences, levels of progress and subject matter, you’ll need to select a variety of assessment types to suit their needs. A quiz might make sense for one subject and group of students, an informal debate for another, KWL charts for younger children, etc. It all comes down to what you think might work best for the group and the content, which takes time and patience to figure out.

Practice and experimentation is key. In time, you’ll be a formative assessment master.

Always test for misconceptions before starting a new unit

Education is a series of building blocks, and if one of those blocks is the wrong size, it compromises the entire structure. Knowledge cannot be built upon if incorrect. If students have misunderstood how basic fractions work, they’re not going to be able to understand equivalent fractions later on.

Thankfully, formative assessments are ideal for diagnosing these kinds of misconceptions. Pretty much any formative assessment can be diagnostic. Whether you’re using surveys, hot seat questioning, or another type of assessment, you’ll quickly discover common misconceptions and remedy them before they can hamper students’ learning later on. And the best time to do this is before starting a new unit, when they’re about to learn fresh content. It’s the perfect time to repair those misshapen blocks of knowledge from the previous unit so you can confidently keep building.

Make students feel safe

Formative assessment can be engaging and highly interactive, so students need to participate for it to work. But this won’t happen unless they feel safe.

Creating a safe learning environment is a big topic, but here are some effective tips you can use to make students feel secure in your classroom, and coax each of them out of their shells:

- Lay down ground rules – make it absolutely clear that there will be no laughing, teasing, or name calling in class, and that transgressions will be punished. These kinds of hurtful interactions can be burned into students’ memories and really hold them back. Make your class a judgment-free zone and enforce a strict zero-bullying policy.

- Be trustworthy – consistently treat your students with kindness, respect and a “fair but firm” attitude, and you’ll quickly win their trust. They’ll feel much safer to participate when they know the authority in the room has their back. This is especially important for the students who are particularly withdrawn or emotional, and may have a turbulent life at home. Your classroom could become their precious safe place.

- Explain the importance of mistakes – every mistake is an opportunity for the student to recognise the error, figure out where they went wrong, and do it right next time. There’s no growth without mistakes – they’re a sign that your students are pushing themselves!

- Incorporate brief social-emotional activities – brief activities like daily greetings, checking in with emotions and gratitude lists can help your students express their emotions to their peers, build stronger empathy skills, and feel emotionally safe in your class.

- Post their work around the class – most of us love to be celebrated for our achievements, and you can do this for your students by posting their great work on the classroom’s walls. It’s a visual reminder that they are skilled and capable.

- Explain why you’re giving an assessment – for formative assessments that can feel high-stakes, like quizzes or one-minute papers, briefly explain why it’s important, and remind them that there are no consequences for wrong answers.

References

- OECD/CERI, Assessment for Learning Formative Assessment, OECD

- Nathaniel von der Embse, Dane Jester, Devlina Roy, James Post, 2018, Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review, Journal of Affective Disorders

- Ian Clark, 2012, Formative Assessment: Assessment Is for Self-regulated Learning, Educational Psychology Review

- Ernesto Panadero, Anders Jonsson, Juan Botella, 2017, Effects of self-assessment on self-regulated learning and self-efficacy: Four meta-analyses, Educational Research Review

- Beaton, A.E. et al. (1996), Mathematics Achievement in the Middle School Years, Boston College, Boston, MA.

- Black P. and D. Wiliam (1998), Assessment and Classroom Learning, Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice

- Steve Graham, Michael Hebert, and Karen R. Harris, Formative Assessment and Writing, The Elementary School Journal

- Hansol Lee, Huy Q.Chung, Yu Zhang, Jamal Abedi, Mark Warschauer, 2020, The Effectiveness and Features of Formative Assessment in US K-12 Education: A Systematic Review, Applied Measurement in Education

- Brown et al. (2014), Make It Stick, Belknap Press

- Catarina Andersson, Torulf Palm, 2017, The impact of formative assessment on student achievement: A study of the effects of changes to classroom practice after a comprehensive professional development programme, Learning and Instruction, 49

- Jens G. Klinzing, Niels Niethard, Jan Born, 2019, Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep, Nature Neuroscience

- Edwin A. Locke, 1968, Toward a theory of task motivation and incentives, Organisational Behaviour and Human Performance

- Hattie, J & Timperley, H, 2007, The Power of Feedback, Review of educational Research Vol. 77

- Carol Dweck, 2006, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, Random House

Nardin is a former primary school teacher of 10 years. During her time as a teacher, she served as Head of Years for K-2, was a trained NAPLAN marker, and was part of the team that wrote the 2021 NSW English Syllabus 3-6. She is currently an assessment consultant for ICAS and Reach.

Written by Nardin Hanna

Written by Nardin Hanna