Standardised assessments: the ultimate guide for teachers

For hundreds of years, countless students have sat at wooden desks and toiled their way through standardised assessments.

As standard tests sat under standard conditions, they’re the only type of assessment that allows educators to measure and compare student performance fairly (as fairly as possible, at least). They’re not without their faults, but they’re the best we’ve got.

In this article, we’ll talk about the fundamentals of standardised assessments, why schools and governments use them, their pros and cons, and more.

What are standardised assessments / tests?

Standardised assessments are tests that are the same (or directly equivalent) for every student. Standardised simply means “made standard” – every child takes the same test, with the same questions, under the same conditions. The tests allow teachers, schools, and governments to evaluate and compare student performance more accurately, though there are many factors that affect the accuracy. Most formal sit-down tests given to school students are standardised.

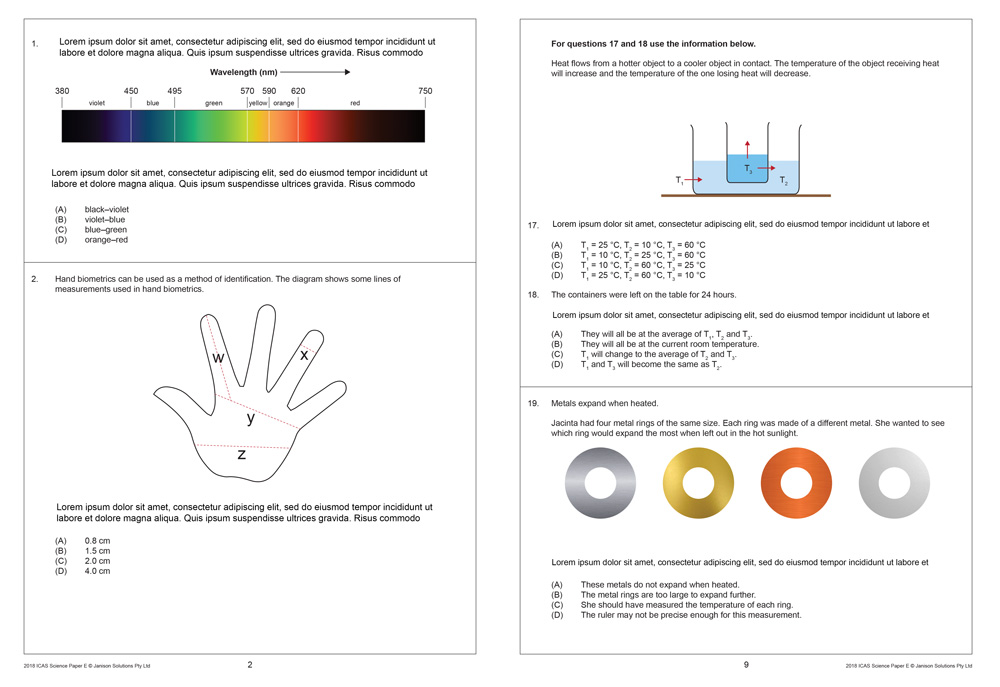

The ICAS competition is a series of standardised tests

The ICAS competition is a series of standardised tests

Consistency is the defining component of standardised testing. A standardised assessment for students should have the same:

- Questions – to compare student performance, they must be tested on the same content. That means each test has the exact same questions of the exact same style – multiple-choice, essays, etc. There can be a mixture of styles in the test itself, but they should remain consistent for every test-taker. Branching tests like NAPLAN are an exception to this, which present students with different questions depending on whether they answered them correctly. But ultimately, the results the questions provide are designed to be directly comparable.

- Style – there are three main styles of test (standardised or not): written, oral, and practical. These styles must be consistent for all students taking the test.

- Marking criteria – the same marking criteria must be used for every test, to ensure scores are consistent and fair.

- Format – the test should be either digital or paper-based for every student, with the same design and layout. Some tests like NAPLAN are delivered using both formats, in which case care needs to be taken to ensure the results are comparable.

- Time to complete – it would hardly be fair to provide one group of students with 45 minutes to complete the test, and another group an hour. So every student should have the same amount of time to finish (unless accommodations are made, more on these below).

- Instructions – every student should have the same written or oral instructions that explain how to complete the test.

- Tools – some tests might require tools such as calculators, protractors or dictionaries. All students should have access to these tools, or the option to bring them along.

- Teacher support – invigilators cannot give preferential support to certain students. They can only clear up confusion around how to complete the test, not provide clues on the content itself.

Accommodations

Some students have genuine obstacles to learning and need extra support to make the tests more equitable, so there are exceptions to some of these components – called “accommodations.” Common examples are more time to complete the tests, test designs that are larger or use different colours for those with vision impairments, and tools like calculators. Students who need these extra things aren’t starting from the same/similar point as other students, so the standardised test only becomes fair and equitable once they are provided with such accommodations. These are usually much easier to implement for online assessments rather than paper-based tests.

Some disadvantaged students may need extra support for standardised tests or changes that make them more equitable

Some disadvantaged students may need extra support for standardised tests or changes that make them more equitable

“Consistency is the defining component of standardised testing.”

As you might expect, non-standardised tests are inconsistent in any of the ways described above. A test may have unique questions, be in a different format, or be marked differently to other tests, in which case you can’t fairly compare them. Examples are student portfolios, group discussions and interviews.

Types of standardised tests

Most types of assessment can be standardised provided they’re delivered in a consistent, standard way for students. This includes exams, pop-quizzes, essays, oral tests, skills tests and more (common examples below). But exams tend to be the standardised test of choice, with NAPLAN the most famous example in Australia. End-of-year exams are also popular with schools for grading purposes.

Standardised tests can be low-stakes or high-stakes. NAPLAN for example, while considered by some to be a high-stakes test, is technically low-stakes because it isn’t intended to have significant consequences on students’ future opportunities (though schools can use the results in ways that make them high-stakes). It’s simply a tool the government uses to measure literacy and numeracy levels to help them write better education policies. Genuine examples of high-stakes standardised tests are the Senior Secondary School Certificate tests that students take from Year 10 onwards that affect their OP and ATAR scores, which define their prospects for tertiary education.

“NAPLAN is technically a low-stakes test because it doesn’t have significant consequences on students’ futures.”

Standardised assessments tend to be summative, evaluating student performance after teaching has finished. But they can also be formative and help to guide your teaching strategies, with common examples being pop-quizzes, the traffic light system, or simply asking questions to the class.

Types of standardised assessments grades/scores

Standardised assessments are graded using two common methods:

Criterion-referencing

With criterion-referencing, tests can be graded using a common scale/standard. Here’s a simplified example:

- 0 to 25 marks = D grade

- 26 to 50 marks = C grade

- 51 to 75 marks = B grade

- 76+ marks = A grade

Students always neatly fall into a grade/band (the criterion), regardless of how other students perform. This type of grading is used to systematically measure students’ skills or knowledge, typically to gauge their learning progress and make adjustments to teaching. They are used as a guide to determine next steps for teachers. Our progress monitoring tool Reach is a good example of a criterion-referenced standardised test.

Norm-referencing (percentiles)

Norm-referenced tests are scored based on how other students performed, using percentile ranks. Here’s an example taken from the ICAS competition:

- Top 1% of scores = high distinction

- Next 10% of scores = distinction

- Next 25% of scores = credit

- Next 10% of scores = merit

- Remaining scores = participation

As you can see, scoring is relative and based on the results of other students. This means students can achieve an objectively low score, but if their peers also performed poorly, they may still fall into an average ranking.

Norm-referencing is used when you want to make comparisons between large groups of students (you need large numbers to achieve statistical significance). NAPLAN uses norm-referenced scaled scores which allow the government to compare relative school performance across the country, as well as norm-referenced achievement bands which give schools useful data they can use to inform their teaching strategies.

Both criterion-referenced and norm-referenced tests may break down results into sub-topics or sub-skills, allowing teachers to understand performance more precisely. For example, a Mathematics test may evaluate student performance for specific skills like algebra or measurements.

Pros and cons of standardised assessments

“Standardised tests help teachers to identify potential learning gaps for students (or groups of students). They can pinpoint content that students are having trouble with and re-teach it in class.”

Standardised assessments are a core staple of modern education, used in countries around the world (OECD, 2011)2. They provide real value to educators but it’s important to understand both their upsides and downsides.

Here are the most common pros and cons of standardised tests.

Pros

- Allow teachers and school leaders to objectively measure student performance, and whether they are progressing quickly enough. For school leaders, they can use this information to assess the school’s general performance and figure out whether changes need to be made to their teaching programs, such as providing additional support to struggling cohorts or teachers. Teachers can look at the standardised test results in more detail and identify which of their specific classes or students are falling behind, and intervene before it starts to really impair their education.

- Help teachers to identify potential learning gaps for students (or groups of students). By analysing the results more closely, teachers can pinpoint content that students are having trouble with and re-teach it in class.

- Allow governments to objectively measure student performance. This helps them to identify where funds need to be channelled and whether improvements need to be made to educational policy.

- Allow parents to gauge their children’s performance against others. Standardised tests that are completed by lots of students (like NAPLAN or ICAS) tend to allow this, helping parents to understand where their children are situated and how quickly they’re progressing compared to others.

Cons

Standardised tests can be worrying for some students, especially those that are high-stakes

Standardised tests can be worrying for some students, especially those that are high-stakes

- They measure performance on one specific day, degrading their reliability. Just because a student performs poorly on one day, doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll perform poorly another day. There are various factors that can temporarily affect test performance – poor quality sleep (Ahrberg et al., 2012)3, unhealthy foods (Taras 2009)4, anxiety (Cassady and Johnson, 2002)7, being bullied (Lacey and Cornell, 2013)5 and many more.

- Test scores are influenced by factors outside of students’ control. Differences in item sampling, rater (marker) agreement, and the tests’ lengths and formats have all shown to reduce reliability for standardised assessments (Le and Klein, 2002)8.

- The tests may not be suitable for all students. Some students may have learning disabilities or challenges that makes the test unfair for them. These can be mitigated with accommodations like extra time to complete the test, but may not be sufficient to make the exam equitable.

- They can make students anxious. Test anxiety can have significant effects on students’ well-being (Soares and Woods, 2019)9, with the potential to affect their test scores (Embse et al., 2018).1 And if students receive low test scores, this might also affect their self-esteem and confidence going forward.

- They can encourage “teaching to the test,” with teachers aiming for good memory recall rather than deep understanding and progress. This is more likely to apply to teachers and school leaders whose performance is measured on their students’ standardised test scores.

- Less time for actual teaching. Time spent preparing for and running standardised tests cuts into teaching time and also adds more work for teachers who are already run off their feet.

“Just because a student performs poorly on a standardised test one day, doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll perform poorly another day.”

Examples of standardised tests in Australia & New Zealand

In Australia, some of the most common examples of standardised assessments for K-12 students include:

NAPLAN & PAT

The biggest annual standardised assessment in Australia, testing students on their foundational literacy and numeracy scores. As a mandatory, nationwide test, it naturally has its promoters and detractors. But regardless of your opinion on the assessments, the data they provide to teachers can be useful, helping them build stronger pictures of their students’ academic progress.

New Zealand doesn’t have a mandatory standardised assessment like NAPLAN, but its educational research council (NZCER) does provide Progressive Achievement Tests (PATs) which assess similar foundational skills, and are popular with schools.

Senior secondary school certificate

These are the graded courses and units that Australian Year 11 and 12 students take that determine their opportunities for tertiary education. They change depending on each state (HSC for NSW, VCE for Victoria, QCE for Queensland, etc.) but all have the same purpose: to assess and grade student academic performance during their closing years of senior secondary school.

In New Zealand, the equivalent is the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCE).

Benchmarking / progress monitoring assessments

Benchmarking assessments are periodic tests (usually annually) that allow you to track your students’ progress over time compared to benchmarks. These benchmarks could be your based on your class, your school, or thousands of other students across the country. They give you an accurate, objective understanding of how your students are progressing, their learning gaps and misconceptions, and what changes you need to make to get them on track.

Check out our version: Reach.

Placement tests

Placement tests are designed to test students’ proficiency for a subject, to determine whether it meets the entry requirements for a university or other tertiary education institution. Each institution has their own criteria, and the tests are often administered by them directly to find suitable students for their programs.

Scholarship tests

Scholarship tests are usually completed by bright students with a good chance of achieving high scores

Scholarship tests are usually completed by bright students with a good chance of achieving high scores

Scholarship exams are notoriously tough standardised tests that are intended to find the most knowledgeable and skilled students for scholarships. They are available for a variety of subjects and allow educational institutions like schools, colleges and universities to differentiate between high-performing students, and which of them should be chosen for their prized scholarships.

Academic competitions

Academic competitions are designed to challenge and motivate students to be the best they can be, in a competitive environment that is similar to sports. They are a series of standardised, tough tests designed to push students to their limits and show them what they’re made of, with the chance to win accolades like medals.

ICAS is our historic academic competition, taken by 100,000+ students each year.

Love them or hate them, standardised tests are here to stay. They’re the most accurate method we have for objectively measuring student performance, allowing you to make better decisions for your students.

Thanks for reading, we hope you found our article useful!

References

- Nathaniel von der Embse et al., 2018, Test anxiety effects, predictors, and correlates: A 30-year meta-analytic review, Journal of Affective Disorders

- Allison Morris, Student Standardised Testing: Current Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review, OECD Education Working Papers

- Arhberg et al., 2012, The interaction between sleep quality and academic performance, Journal of Psychiatric Research

- Taras, 2009, Nutrition and Student Performance at School, Journal of School Health

- Lacey and Cornell, 2013, The Impact of Teasing and Bullying on Schoolwide Academic Performance, Journal of Applied School Psychology

- House of Commons (2008), Testing and Assessment, Volume 1, The Stationery Office Limited, London

- Cassady and Johnson, 2002, Cognitive Test Anxiety and Academic Performance, Contemporary Educational Psychology

- Le, V. and S. Klein (2002), Technical Criteria for Evaluating Tests, Making Sense of Test-Based Accountability in Education

- Soares and Woods, 2019, An international systematic literature review of test anxiety interventions 2011–2018, Pastoral Care in Education

Tag:assessments